Children and teens often don’t recognize their anxiety for what it is. Instead, they may think there is something “wrong” with them. Children may focus on the physical symptoms of anxiety (e.g. stomachaches). Teens may think they are weird, weak, out of control, or even going crazy! These thoughts might make them feel even more anxious and self-conscious. Therefore, the first step is to teach your child about anxiety and how to recognize it. Self-awareness is essential!

On this page: |

The facts

Myth: Talking to your child about anxiety will make them even MORE anxious.

Fact: Providing accurate information about anxiety can reduce confusion or shame. Explain that anxiety is a common and normal experience, and it can be managed successfully! Once your child understands this, he or she will feel more motivated to make life easier.

How to do it

There are three steps to introducing the topic of anxiety to your child:

- Step 1: Encouraging your child to open up about any fears and worries

- Step 2: Teaching your child about anxiety

- Step 3: Helping your child recognize anxiety

Step 1: encouraging your child to open up about worries and fears

-

Start by describing a recent situation when you observed some signs of anxiety in your child. “Yesterday, when Sarah came over, you seemed very quiet and you just sat beside Mom. It seemed you may have been a bit nervous about having a visitor in our house. What was that like for you?”

-

Tell your child about some things you were scared of when you were the same age (especially if you shared the same types of fears), and ask if he or she has any similar worries or fears.

Ask what worries him or her the most.You may have to prompt younger children by offering an example such as: “I know some kids are scared of ___, do you have that fear too?” Being specific can help your child sort through confusing fears and feelings.

-

When your child expresses anxiety or worry, offer reassurance by saying you believe him or her, and that having those feelings is okay. Remember, your child will take cues from you.Show acceptance of worry thoughts and anxious feelings. If you stay calm, it will help your child stay calm, too!

Tip

Does hearing “Don’t worry. Relax!" help you when you're anxious about something? It probably doesn't comfort your child much, either. It’s important to acknowledge that your child’s fears are real. Your empathy will increase the chances that your child will accept your guidance, and discuss his or her fears with you in the future.

Step 2: teaching your child about anxiety

The following two videos summarize the main points below that can help educate your child or teenager about the fight or flight response:

Four important points to communicate to your child:

1. Anxiety is normal

Everyone experiences anxiety at times. For example, it is normal to feel anxious when on a rollercoaster, or before a test. Some teens may appreciate some facts about how common anxiety problems are. For example, “Did you know that one-in-seven children under 18 will suffer from a real problem with anxiety?”

2. Anxiety is not dangerous

Though anxiety may feel uncomfortable, it doesn’t last long, is temporary, and will eventually decrease! Also, most people cannot tell when you are anxious (except those close to you such as your parents).

3. Anxiety is adaptive

Anxiety helps us prepare for real danger (such as a bear confronting us in the woods) or for performing at our best (for example, it helps us get ready for a big game or speech). When we experience anxiety, it triggers our “fight-flight-freeze” response and prepares our bodies to defend themselves. For instance, our heart beats faster to pump blood to our muscles so we have the energy to run away or fight off danger. When we freeze, we may not be noticed, allowing the danger to pass. This response is also called “anxious arousal”. Without anxiety, humans would not have survived as a species!

-

How you can explain the fight-flight-freeze response to a child:

“Imagine you are hiking in the woods and you come across a bear. What is the first thing you would do? You may run away from the bear, or you may simply freeze. Another reaction is to yell and wave your arms to appear big and scary. There are three ways humans react to danger: fight, flee, or freeze. When we are anxious, we react in one of these ways, too. We may run away or avoid situations that make us anxious. Or we may freeze, such as when our minds go blank and we can’t think clearly. Or we may fight, get angry and lash out at people. Can you think of some ways you may fight, flee, or freeze because of anxious feelings?” -

How to explain “anxious arousal” to a teen:

Sometimes when we sense something is dangerous or threatening, we automatically go into a state called “anxious arousal”. This can happen when there is a real danger, but also when something simply feels dangerous, but really isn’t, such as giving an oral presentation in class, or...(give an example of something relevant to your child). Anxious arousal makes you feel jittery, on edge, and uncomfortable. It may also make it hard to think clearly. This feeling can become overwhelming enough that anxious people stop doing things or going places that make them feel anxious. Do you think this is happening to you?

4. Anxiety can become a problem

Anxiety can become a problem when our body reacts as if in danger in the absence of real danger. A good analogy is that it’s like the body’s smoke alarm.

-

How you can explain the “smoke alarm” response:

“An alarm can help protect us when there is an actual fire, but sometimes a smoke alarm is too sensitive and goes off when there isn’t really a fire (e.g. burning toast in toaster). Like a smoke alarm, anxiety is helpful when it works right. But when it goes off when there is no real danger, then we may want to fix it.”

More about How Anxiety “Works”

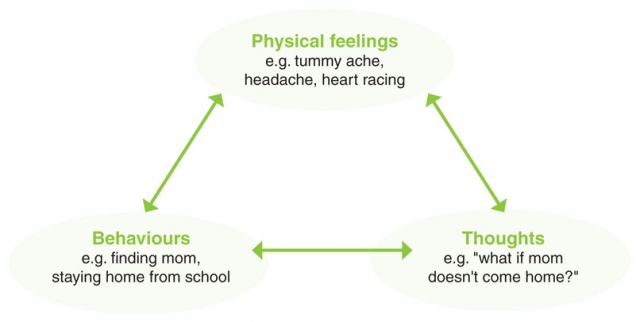

Explain to your child the three parts of anxiety: thoughts (what we say to ourselves); physical feelings (how our body responds); and behaviours (what we do or our actions). A good way to describe the interconnection of these parts is to draw a triangle with arrows (see figure below).

Step 3: helping your child recognize anxiety

For younger children, talk about how you will both be “detectives”, and how you will help your child in an “investigation” to find out more about anxiety. As detectives, find examples of how your child experiences anxiety in each of the three parts: physical symptoms, anxious thoughts, and avoidance behaviours.

Being a detective: recognizing physical symptoms

To help your child recognize physical symptoms, draw a sketch of a body and ask your child to identify where he or she feels anxiety in the body. Prompt your child, if necessary, with an example: “When I feel anxious, I get butterflies in my tummy, and I get a big lump in my throat. What happens when you feel anxious?” Have your child lie down on a large piece of paper (e.g. butcher’s paper) and trace his or her body. You can also print and fill out Chester the Cat (download at www.anxietycanada.com) for young children. Teens may rather just talk about it, or identify their own symptoms from a list of “typical” physical symptoms.

If age-appropriate, ask your child to come up with a name for anxiety (e.g. Mr. Worry, Worry Monsters). Refer to your child’s anxiety with this new name, particularly in terms of “bossing back” anxiety (e.g. “It’s just the worry monster talking. I don’t have to listen!”). Older children or teens may respond better to a music analogy, such as that the volume of their anxiety is “turned up” a bit louder than other kids. They simply need to learn to turn down the volume.

These strategies help your child adopt an observer role when dealing with anxiety, giving them a greater sense of control.

Being a detective: recognizing anxious thoughts

Younger children may sometimes have difficulty identifying their thoughts, and especially anxious thoughts. For more information, see Healthy Thinking for Young Children at www.anxietycanada.com.

Older children and teens will likely be able to identify some of their anxious thoughts, and even challenge their unrealistic thoughts. For more information, see Realistic Thinking for Teens at www.anxietycanada.com.

Regardless of your child’s age, help your child understand that anxiety, and not actual real danger, is causing him or her to miss out on important opportunities and fun events.

Being a detective: recognizing avoidance

Ask your child to come up with as many answers as possible to the following:

- If you woke up tomorrow morning and all your anxiety had magically disappeared, what would you do?

- How would you act?

- How would your family know you weren’t anxious? (Your teacher? your friends?)

Finish the following sentences:

- My anxiety stops me from...

- When I am not anxious, I will be able to...

Once your child has gone through these three steps, and is able to understand and recognize anxiety, your child will be better prepared to move on to the next stage—learning how to manage anxiety!

About the author

Anxiety Canada promotes awareness of anxiety disorders and increases access to proven resources. Visit www.anxietycanada.com.

Thank you to Anxiety Canada's Registered Clinical Counsellor and Clinical Educator, Mark Antczak, for reviewing this resource in 2022.