A health promotion perspective

Health is a state of physical, mental, social and emotional well-being. Health promotion encourages us to embrace this idea of well-being and in the process increase control over our everyday lives and reach toward our full potential. How does this work?

Effective health promotion balances individual and community needs, rather than placing responsibility only on the individual. It pushes us beyond a disease-oriented "individual lifestyle is key" idea of good health to focus attention on the social, economic and environmental factors that impact our attitudes, decisions and behaviours. These factors affect every level of society, from the individual through the family and community to a national and even global scale.

This perspective can be applied in a variety of settings, including workplaces, neighbourhoods, cities, and schools or campuses, to find ways we can improve our everyday life and feeling of well-being. Health promotion is also applied to common but complex human behaviours such as substance use.

Health promotion and substance use

Like food, sex and other "feel good" things in life, psychoactive substances (drugs) change the way we feel. Using substances has both benefit and a potential to lead us down an unhealthy path, getting us into trouble with our health, relationships, and sense of self-worth. It is important to view substance use from a broad perspective that considers many factors, rather than simply personal ones such as pain relief, managing difficult feelings, wanting to feel good or doing better at an activity.

The substance use field has generally focused on ways to measure, prevent and treat negative effects of using substances. This has led to a continuum of laws, policies, and services that restrict the supply of drugs, reduce drug demand or in some cases, reduce the harms that may be experienced from drug use.

Supply reduction:interventions that restrict access to a substance (particularly for populations considered vulnerable to harm) |

Demand reduction:services to reduce the number of individuals who use substances, the amount they use or the frequency of use |

Harm reduction:interventions that seek to reduce the harmful consequences even when use remains unchanged |

Versions of this continuum have been used for some time. All begin with a disease or harm that should be avoided. While this may seem to make sense, it is less clear when we consider that many people use psychoactive substances to promote their physical, mental, emotional, social or spiritual well-being. Further, it is worth noting that of those who use substances only a small percentage experience problems with their level of use. Simply put, people use substances to promote health, yet substance use services often focus on how drug use detracts from health. Rather than focusing on protecting people from disease or harm, health promotion seeks to enable people to increase control over their health whether they use substances or not.

A more human approach

Human experience is complex and often challenging to understand. Helping people make sense of their experience, and giving them skills to manage it, helps them take charge of their lives, rather than be victims of it. The poet John Donne said, "No man is an island, separate unto itself. Every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main." A health promotion analogy might suggest that though we make individual decisions, those decisions are made within and influenced by the context in which they are made. Our biology, physical and social environments and events throughout life are among the factors that influence behaviours and choices. Institutional (e.g., hospitals, schools) and community culture, as well as family and societal values, also influence behaviour and its impact on overall health. These factors interact in a way that creates a unique set of opportunities and limitations for each of us as we move through our daily lives.

Substances:regulate supply to ensure the quality of substances and enact appropriate restrictions |

Environments:physical contexts that encourage moderation and are stimulating and safe |

Individuals:increase health capacity and resilience and develop active responsible citizens |

People have been using a wide variety of psychoactive (or mind-altering) drugs throughout history...

Therefore, health promotion for people who use substances involves helping them manage their substance use in a way that maximizes benefit and minimizes harm. This is how we address other risky behaviours in our lives, including driving and participating in sports. It means giving attention to the full picture—the people—where they live, how they use substances, and how all these are shaped by the environments and factors surrounding them.

People and drugs

Drug use is deeply embedded in our cultural fabric. People have been using a wide variety of psychoactive (or mind-altering) drugs throughout history to celebrate successes, help deal with grief and sadness, to mark rites of passage such as graduations and weddings and seek spiritual insight. Using drugs also involves risk.

Caffeine, alcohol and other psychoactive drugs influence the way nerve cells send, receive, or process information in our brains. Using drugs can be risky and associated with significant harm. The short-term intoxicating properties of psychoactive drugs tend to be acute or immediate, and may be lower (e.g., hangover) or higher risk (e.g., participation in unplanned sexual encounters). Other harms relate to chronic conditions (e.g., heart disease, cancers) that can emerge from longer term use. Harms vary depending on characteristics of the drug itself, how it is taken, or the setting in which use takes place. For example, much of the chronic harm related to tobacco is from inhaling the smoke rather than from the drug (nicotine) itself.

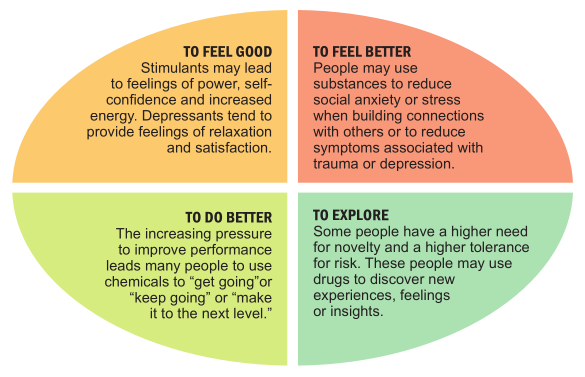

People use substances...

To feel good

Stimulants may lead to feelings of power, self-confidence and increased energy. Depressants tend to provide feelings of relaxation and satisfaction.

To feel better

People may use substances to reduce social anxiety or stress when building connections with others or to reduce symptoms associated with trauma or depression.

To do better

The increasing pressure to improve performance leads many people to use chemicals to "get going" or "keep going" or "make it to the next level."

To explore

Some people have a higher need for novelty and a higher tolerance for risk. These people may use drugs to discover new experiences, feelings or insights.

Depressants:decrease heart rate, breathing and mental processing—for example, alcohol and heroin |

Stimulants:increase heart rate, breathing and mental processing—for example, caffeine, tobacco or cocaine |

Hallucinogens:make things look, sound or feel different than normal—for example, magic mushrooms or LSD |

Substance use and risk

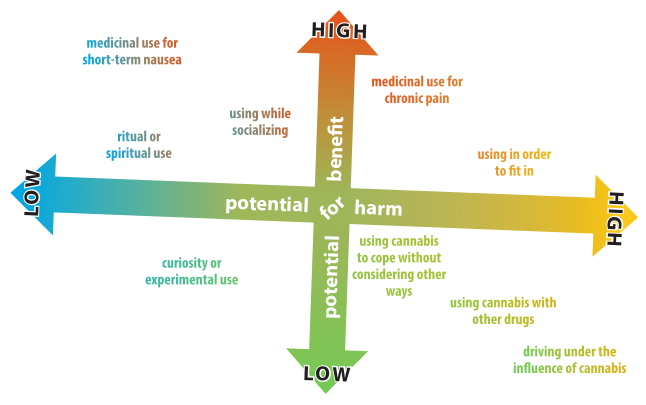

Why we use a drug influences our pattern of use and risk of harmful consequences.

Using a drug because we are curious, or for another passing reason, often results in occasional or experimental use. If we use a drug for a stronger or ongoing reason such as poor sleep or a mental health concern, then more intense and long-lasting use may result. Reasons for intense short-term use such as fitting in with peers, having fun or reducing temporary stress such as school exams, may result in more risky behaviours and greater potential for acute harm. Examples here include driving while intoxicated or overdosing on an unknown drug.

Certain places, times and activities also influence our substance use patterns and the possibility of experiencing harm. For example, unsupervised teen drinking tends to be an extremely high-risk activity. Being under the influence of alcohol or antianxiety drugs (e.g., benzodiazepines) in a difficult social situation can increase the likelihood of a conflict becoming violent. Drinking or using drugs before or while driving, boating, or hiking on dangerous terrain increases the risk of injury. Drinking can also lead to unplanned, unprotected, or unwanted sexual encounters that may result in an STI, pregnancy or rape.

The social and cultural context in which we use drugs is often more important than we think. For example, the cheaper and easier it is to get a drug, the more likely it is to be used. Community norms also influence individual behaviour. General social acceptance of alcohol, coupled with easy access to a safe and regulated supply, along with reasonable cost contribute to extensive alcohol use in Canada. Our degree of connection to family, friends and the wider community can impact how much, how often, when, where and how we use different substances. Attitudes to substance use is also important. If alcohol is not accepted within our family or cultural group, then we are less likely to use, or even try it.

Personal factors also affect our likelihood of using drugs in risky ways. If we struggle with anxiety or depression, for example, we may try to feel better by drinking alcohol. Sometimes, difficult life experiences (e.g., physical, sexual, or emotional abuse) impact our physical and mental health and can contribute to potentially risky drug use. Evidence suggests that inherited factors and personality or temperament may affect our tendency to use substances, and do so in potentially more risky ways. For example, people who commonly seek out intense and varied experiences are at higher risk of harm. The chemical composition and purity of a drug, along with the amount, frequency, and method of consumption, also influence the degree of risk and type of harm we might experience. Depressant drugs such as alcohol or heroin have elevated risks for overdose, for example, whereas intense use of stimulants can lead to psychotic behaviour for some people (see graphic on previous page).

How drugs can affect our brain

When our brain is repeatedly exposed to a drug, it can respond in several ways in an attempt to re-balance itself. It may become less responsive to a particular chemical (drug, or component of a drug) so that natural "feel good" sources such as exercise, food, sex, and hobbies, provide little pleasure and we feel 'flat' and depressed. As a result, we may need to use drugs to feel normal and need larger and larger amounts to feel okay. This is known as becoming tolerant to a drug. Resulting brain changes may lessen our ability to think clearly or move our bodies well.

Conditioning, or linking things in our environment with our experiences of a drug, is another common effect of repeated drug use. Encountering these cues, or triggers in the environment, can cause intense cravings. Drinking coffee and smoking is a common example of one psychoactive substance triggering use of another. We might also associate the end of a workday with going out for a beer. Our minds and bodies can become so adapted to these patterns that we may be uncomfortable when we try to break the routine.

A word about addiction

A common notion in our culture is that some drugs are naturally dangerous and can somehow control our behaviour. According to this idea, a person takes a drug until one day, the drug takes the person. Once this shift occurs, a person is characterized as "addicted" and unable to control their substance use. An image that too often comes to mind when we think about addiction in this way is someone who is overwhelmed by their substance use, unemployed, possibly homeless and disconnected from family and friends. How accurate is this stereotype?

We may know people who seem unable to control their drinking or drug use. We may feel powerless in some circumstances or at certain times. Does this feeling of powerlessness mean the drug or some other force is actually controlling us? If so, how should we understand people who quit using a substance after years of use? Many people, for example, successfully quit smoking simply by deciding one day not to buy any more cigarettes.

A more compassionate and realistic perspective places the focus on the person. It considers the context and reasons why we start and continue to use drugs, rather than just thinking about the drug itself. In focusing on the person, we are also reminded that we are all human, and any circumstance or outcome of substance use may just as easily become our own experience. How might we better understand this perspective?

Putting the person first can work for all of us

If we think about substance use from a "person first" point of view, risky or potentially harmful behaviour may be seen as a way of coping with a situation or condition. This approach can help us better understand life situations and experiences that do not easily t a narrow view of "addiction." For instance, it helps us understand how some people who inject drugs can and do continue to work and maintain a job, a family, and other important relationships. It can also help us understand that homeless people may use substances as a way to cope with extreme poverty, trauma or horrific living conditions.

One of the best reasons for adopting a "person first" perspective on substance use is our human need to reach out to others. When we see others as having a disease or influenced by something we do not understand, we can see them as "broken" or "alien" and not like us. We may label them "alcoholic" or "addict," terms more about a substance than another human being. When we adopt a view which takes into account a range of factors—from biological to social and environmental—we see just another person who uses substances within certain contexts and for specific reasons. In other words, we see someone more like us.

When we see others as more like us, especially as we reflect on our own life experiences, we begin to understand why some people may feel dependent on a substance to cope with something in their life and why they may feel unable to give it up. Focusing on the person rather than the drug helps us reach out to someone who may appear unable to control their substance use. "Person first" also offers a way to support someone doing well but who regularly uses drugs in harmful ways. In both cases, we arm the person's ability to make decisions and care for themselves rather than as a victim, inferior, or less human than us.

A socio-ecological model and "frogs in a pond"

One way to visualize substance use from a health promotion perspective is to consider a "frogs in a pond" scenario. If the frogs in a pond started behaving strangely, our first reaction would not be to punish them or even to treat them. Instinctively, we would wonder what was happening in the pond—in the soil or water, with the plants or among the other inhabitants, that was affecting the frogs. The same ecological approach is usefully applied to substance use.

The "pond" represents our children, friends, family, neighbours and coworkers, along with a specific set of opportunities and constraints related to our biology, relationships and environment that influence each of us in our daily life. When and how we decide to use or not use a substance depends on a specific mixture of all aspects of the "pond" we live in, along with our needs and desires. In this analogy, the behaviour of a particular frog and the choices they make is not just about that individual, or the pond. It is about all the frogs, the purity and temperature of the water, how much food and sunshine there is, and the predators that may eat them or the diseases that may infect them, everything about the pond. It becomes clear that the pond determines a frog's choices as much as the frog! As the life of one frog in the pond is not just about that frog, a person's substance use is not just about the drug or the person, it is about how all the factors in their life interact in a way that is unique to them. Following this reasoning, what every person needs to do to manage their substance use is specific to them.

If we think of substance use within this socio-ecological frame, it takes the focus away from the substances. It helps us step back and look at the whole picture or the "ecosystem" in which each of us functions. A socio-ecological model also includes paying attention to the environments in which behaviours and skills play out. This provides a way to reflect on how individual, societal and environmental factors influence and feed back on one another.

While our personal role is always critical, the factors that influence our health and wellness go well beyond individual choices or capacities. For instance, the risk and protective factors that impact resilience, our ability to rise above or bounce back from adversity, do not reside only within ourselves. Many of the most important factors relate to our relationships (e.g., family, friends), aspects of our community environment (e.g., norms, availability of alcohol and other drugs) and our social location (income and social status). Our personal and community environments play key roles in the choices we make and the outcomes we experience.

Substance use, risk, harm, and the human "pond"

Humans are indeed complex beings. Many of the things that influence us interact with one another. Under some conditions, something might have a different influence on us than it would under other conditions. For example, a child living in a stressful family environment who regularly witnesses their parents drinking alcohol to cope with life issues may learn that using alcohol is a reasonable way to deal with problems. Unfortunately, this can lead to the child using alcohol in risky ways later in life. Such a difficult environment can also compromise the child's ability to experience or learn strategies and habits that promote health and well-being. However, community norms that promote moderate alcohol consumption and a mentoring program are two ways youth could learn healthy coping strategies and habits that may help lessen risky alcohol use. It can work the opposite way as well.

In a community where risky drinking or drug use is normal and there are few supports, the outcomes for young people and their community may be very different. A youth with fewer coping skills may do quite well in a familiar environment but suddenly become angry when confronted with a situation that feels threatening. For example, a young person may easily say "no" to someone who offers drugs at school, and feel backed up by friends and family. If that young person moves to a new school where they don't know anyone and are similarly approached, they may have more diffculty. An unfamiliar environment, little knowledge of rules in the new school and lack of peer support, may lead to the youth becoming upset and lashing out or purchasing unwanted drugs. They may get into trouble with peers, the school, and the law. This behaviour is not just about individual capacity. Environmental factors—school policies and information sharing processes, local law enforcement practices, and level of personal support, all influence immediate behaviours and contribute to the development of current and future capacity to manage substance use.

The effects of biological, social and environmental factors play out our entire lives, no matter which “pond” we live in. The younger a person is when they begin regularly using drugs or use significant amounts of drugs, the more likely they are to experience harms or have problems with substance use later in life. Similarly, people who experience repeated trauma early in life are more likely to experience a wide range of problems later on. Life transitions (e.g., entering high school or university, getting married) can increase our vulnerability and add to challenges an individual already faces. Though personal supports and resources can contribute to well-being at any time along the life course, access to these resources in early childhood can help us more easily face challenges at all stages of life.

People make places, and places make people

Our communities are social ecosystems where a variety of factors interact to influence the health of the environment and the people living in it. Improving our health involves influencing our actions, enhancing our capacities, and ensuring there are opportunities for all individuals and institutions in our communities to improve their health. One way we can do this is to collectively recognize substance use as a complex and very human behaviour, then moving beyond acceptance to managing the risks and harms related to use. This is both an individual and social responsibility. When used with care, many psychoactive drugs can be beneficial. That is, the positive impact may outweigh the risks involved. When used without care or in the wrong contexts, risks can quickly outweigh benefits.

Managing risk and reducing harm—whether it involves substance use or other common but risky human behaviours requires examining our reasons or motivations for a behaviour and assessing the risk and protective factors in play. Individuals can engage in self assessment and moderate their substance use (not too much, not too often). Communities can contribute to reducing the risks and harms related to drug use by promoting a culture of inclusivity for all citizens, mutual responsibility and by addressing social and economic conditions that can lead to risky drug use.

A word about language

Words have the potential to affect how we feel about ourselves and other people. We all have opportunities to change the way some terms are used and help shape language that promotes inclusion rather than exclusion. What can you do to help?

Use simple, general language. Whenever possible, use broad terms (e.g., substance use, substance-related harm). This avoids labelling individuals and introducing emotionally loaded judgements that can increase stigma rather than reduce it. Narrower language (e.g., substance use disorders) can be appropriately used when required in a particular context.

Limit use of negative language. Terms like "substance abuse" have negative moral overtones. Substances cannot be victims and it is not clear who is experiencing the abuse. This term also blames the person using the substance. This is inaccurate and unhelpful and can increase stigma related to substance use rather than decrease it or remaining neutral. Terms such as "problematic substance use," while less overtly judgemental, can still limit discussion and promote a negative focus when balanced language may be more useful. For example, saying that problematic substance use by adults may influence the behaviour of young people does not draw attention to the reality that any pattern of substance use may influence young people (some positively, others negatively).

When referring to someone experiencing substance use issues, again, person first is helpful. The person is experiencing an issue or concern, or may be using substances in potentially risky ways. The person is not a problem; how they are using substances may be a concern they wish to address. A larger discussion of this issue along with some practical ways to assist someone who uses substances is available in Supporting People Who Use Substances: A Brief Guide for Friends and Family.

Health promotion in practice—Policy directions

Ultimately, the goal of health promotion is healthy people in healthy communities. This also applies to using substances. People have been using psychoactive substances for millennia to promote health and well-being, yet these substances cause, or have the potential to cause, harm to individuals and communities. Health promotion in this context is about helping people manage their substance use as safely as possible.

In a healthy community, one goal is often that a majority of people are engaged in health-promoting actions around substance use such as following low-risk drinking guidelines, avoiding smoking and adopting safer use techniques. A variety of motivational strategies and social marketing campaigns supporting healthy behaviours and safer use might be implemented. How well do these inspire reflection and intentionality? Building people's capacity to engage in healthy actions is crucial. This requires a focus on health literacy to increase the number of people who have the knowledge and skills to manage their health effectively and are equipped to help others in the community. Healthy action also requires more than knowledge and skills. It is not enough to encourage people to be healthy if the social or economic conditions in which they live undermine their ability or efforts to engage in healthy actions.

This brings us to the last, and likely, most important element of a healthy community, health opportunities. These are settings where people can take part in and receive benefit from the full range of policies, practices, and strategies offered to promote and support individual and community health. This requires a focus on social justice and health equity. It means advocating for policy that acknowledges the complex circumstances that impact people's abilities and actions.

Policy to address social and health inequities is fundamental and would ensure access to appropriate and adequate housing, income and supports, including health services, for all citizens. Addressing life circumstances also means creating environments where children are free from trauma and support is available for those who are traumatized. Further policy would identify and address other factors that increase the likelihood of substance use issues in youth and adulthood. Health opportunity also means promoting social connectedness through increasing meaningful opportunities for socialization and reducing isolation among all community members. This might be accomplished, at least initially, by fostering greater opportunity for community gatherings to share ideas and develop plans and strategies to accomplish items identified by community input.

From a health promotion perspective, drug education in a healthy community would be more about developing health literacy (the knowledge and skills needed to manage substance use) than about marketing focused on a particular lifestyle. Prevention programs could focus on reducing harmful patterns of use rather than on drug use per se. Substance use treatment services may be re-designed to empower individuals to select their own goals and choose services that meet their individual needs while providing support to develop the personal skills to achieve these goals. Focus would be on developing individual and community capacities, giving adequate attention to both healthy public policy and community action, rather than trying to prevent or "x" problems that many of us mistakenly believe belong to the "other people" in society, rather than all of us.

Resources

Alexander, B.K. (2010). The Globalization of Addiction. New York: Oxford University Press.

Glass, T.A. & McAtee, M.J. (2006). Behavioral science at the crossroads in public health: Extending horizons, envisioning the future. Social Science & Medicine, 62(7), 1650–1671.

Graham, H. (2004). Social determinants and their unequal distribution: Clarifying policy understandings. The Millbank Quarterly, 82(1), 101-124.

Health Council of Canada (2010). Stepping It Up: Moving the Focus from Health Care in Canada to a Healthier Canada. Toronto. https://nccdh.ca/resources/entry/stepping-it-up

Perry, S. & Reist, D. (2006). Words, Values and Canadians. Vancouver: Centre for Addictions Research of BC.

Small, D. (2012). Canada's highest court unchains injection drug users: Implications for harm reduction as standard of healthcare. Harm Reduction Journal, 9, 34.

Stokols, D. (1992). Establishing and maintaining healthy environments: Toward a social ecology of health promotion. American Psychologist, 47(1), 6–22.

About the author

The Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research is a member of the BC Partners for Mental Health and Substance Use Information. The institute is dedicated to the study of substance use in support of community-wide efforts aimed at providing all people with access to healthier lives, whether using substances or not. For more, visit www.cisur.ca.