Understanding the connections

On this page: |

Currently, on any given night, approximately 35,000 people in Canada are homeless. Another 50,000 people are without homes of their own and stay with friends and family for shelter. Another 800,000 Canadian households pay more than 50% of their income on housing costs, putting them at high risk for homelessness. A national poll conducted in July 2020 amid the COVID-19 pandemic, found that 16% of Canadians were worried or somewhat worried about their ability to pay their next month’s housing costs.1

Homelessness is an extreme form of poverty. The Canadian Observatory on Homelessness describes homelessness as

...the situation of an individual or family without stable, permanent, appropriate housing, or the immediate prospect, means and ability of acquiring it. It is the result of systemic or societal barriers, a lack of affordable and appropriate housing, the individual/household's financial, mental, cognitive, behavioural or physical challenges, and/or racism and discrimination. Most people do not choose to be homeless, and the experience is generally negative, unpleasant, stressful and distressing.3

Homelessness is more about the lack of a stable living situation and the conditions that produce that situation than it is about the individual or family who is homeless.

How did we as a society, arrive at the place where so many people are without housing?

Some history of homelessness

Home was not defined as a private space for family life until about 1800. People without homes (and those living in poverty) became increasingly associated with terms such as "homeless," "friendless," and "destitute." Those in poor economic circumstances through no fault of their own might be viewed as deserving help. Paupers (people living in extreme poverty) were often viewed as not deserving assistance because it was assumed, they were lazy or chose not to fit into society. Hobo often described men who travelled to follow work opportunities during the Great Depression of the 1930s. In this case, homelessness was implied to have an element of choice and, therefore, not necessarily deserving of material support. With the Great Depression, even though assumptions about choice and unwillingness to work continued to dominate, homelessness began to be associated with larger economic and societal conditions. Post World War II, with economic conditions improving and technology replacing traveling labourers, the number of people experiencing homelessness declined. Further, the United States and Canada developed housing and welfare programs at this time, in part to assist war veterans in re-establishing themselves and to spur economic growth.

Homelessness as we currently know it emerged in the 1980s. A mix of new political ideals and changes in economic and social patterns started to influence policy in both the United States and Canada—responsibility for social issues was gradually shifted from government to individuals. Conflicting perceptions of people experiencing homelessness emerged. They could be seen as victims of policy changes that limited housing availability and financial supports. Nonetheless, old perceptions of social outsiders unwilling to work persisted. By 2000, homelessness was also consistently linked to illness, including mental illness and substance use disorders.

A significant number of homeless people experience mental health and substance use concerns as well as a range of physical illnesses. Some experience these issues before becoming homeless and others as a consequence of homelessness. In the 1990s, in a process known as deinstitutionalization, many people were discharged into the community from long term psychiatric hospitals in British Columbia. Without adequate housing and community supports, a significant number became homeless. This increase in homelessness and the visibility of homeless people, resulting from changes in the health care system, may have contributed to a softening of political and social attitudes and increased effort to address the needs of homeless people. These efforts, however, are often tied in part to a medical model in which services are dependent on having a medical diagnosis or compliance with other expectations set by professionals.

The idea that people who are homeless require medical intervention remains prominent. Though this is true for some, current best practice is housing people first and then addressing mental health, substance use, and other health concerns in partnership with the individual. This is known as Housing First. The majority of people are homeless for a short time and require only adequate housing, income and, sometimes, health services or other types of support to exit homelessness. A small proportion experience chronic or long-term homelessness that may be linked to mental health and substance use issues and require assistance in dealing with these concerns.

Conflicting understandings of homelessness and people who experience it are prevalent today. These understandings are influenced by a number of factors, including historical notions of poverty and who does or does not deserve public support. Coupled with political choices that result in low levels of income and assistance; a severe lack of affordable housing; and systems such as foster care, that do not adequately support those they are designed to serve, these factors together create homelessness as we know it. In the ongoing economic hardships, isolation, and anxiety surrounding COVID-19, tensions have risen. People who are homeless are often met with fear, ridicule, and contempt, contributing to their exclusion from society through poverty, stigmatization, discrimination, and criminalization of living homeless.

Health and homelessness

How are health and homelessness related?

The health of Canadians is largely shaped by the conditions in which they live. These conditions are increasingly known as the "social determinants of health."† Safe, adequate, affordable housing is a key determinant of health. A lack of affordable housing, along with a primarily market-based pool of rental units, contributes to homelessness and housing insecurity. Many people have to pay a large part of their income for housing. This greatly increases the risk that people in poverty, not currently homeless, may become homeless.

Housing is more than bricks and mortar. It is my/our space. "Home is one of the few places in an individual's everyday life where they are socially and legally allowed complete control."2 Control of housing may mediate or reduce the impact of other factors related to health status. Having a place that is safe from the elements, warm and where you can go in and lock a door behind you, gives the privacy and control that each of us needs to conduct many aspects of life away from the view of those not living in our household. Control of home décor and household chores, friendly neighbours, a sense of belonging and participation in community all contribute to a sense of home that can decrease stress and increase health. Such a private space is also legally different from a shelter or living outside. No one, including the police, may enter your home without permission, unless there is an emergency such as a fire, flood or some form of violence or the police have a court order that allows them to do so. There are no such rights in a shelter, living outside or in rooms rented under the Hotel Keepers Act. Police may enter at the invitation of the service provider, rather than the individual occupying the room, or intervene at any time in a public space.

Income is also a key determinant of health. People with higher incomes and social status have a much greater range of choices for housing, food and education for themselves and their children. Their greater assets and increased options can be used to offset risks that occur in life. People with higher income are less likely to develop illnesses such as cardiovascular disease and Type II diabetes. On the other hand, growing up in poverty is a good predictor of these diseases in adulthood. This is because the relative privilege provided by higher income and status (e.g., quality food, vacations, access to activities and health care), may lessen stress effects across the lifetime, resulting in lowered incidence of disease.

Without adequate housing and income, people who are homeless are at much higher risk for illness and death than those who are housed. This results from the intersection of numerous factors, including living outside or in shelters with others who may be ill, poor nutrition, lack of access to health care and having to choose among essential options such as a shelter bed for the night or adequate food. People who are homeless experience higher rates of cancer, diabetes, tuberculosis, HIV, hypertension (high blood pressure), and dental problems. They are also more affected by lung issues, foot problems and injuries when spending long periods outdoors in harsh weather. The time and effort needed to try and meet basic life needs in a day, often in extreme circumstances, as noted by one recent study participant, makes being homeless "a full-time job."4

Health and well-being are not possible without appropriate housing. Safe, affordable, adequate housing is needed for the growth and development of children, and the ongoing physical, emotional, and psychological health of individuals and families. Housing then is not merely a roof over one's head. It is a critical base from which healthy development and ongoing health and well-being proceed. Without housing, people are unable to improve their life circumstances or social position, including obtaining adequate income. People who are homeless or inadequately housed can only focus on day-to-day survival.

A socio-ecological model of homelessness

According to the World Health Organization, health is a basic human right: "The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition."5 That means we are all responsible to work for the health of all.

To address homelessness, we need to take a holistic approach to human beings and recognize how the environment affects people. The World Health Organization also states that "health is more than the absence of disease: it is a state of physical, intellectual, emotional and spiritual well-being."5 Our communities are social ecosystems where a variety of factors interact to influence the health of the environment and the people who live in them. Improving the health of our communities involves influencing the choices people make, helping people develop the knowledge and skills they need and ensuring the environment provides people with resources and opportunities to live healthy lives.

Using a socio-ecological model helps us step back and look at the whole picture or the ecosystem in which people function. It highlights that each of us is influenced by a unique set of opportunities and constraints shaped by a complex interaction of biological, social and environmental factors that play out over our life course. In other words, it draws attention to the range of influences—from personal characteristics to broad social factors—that shape our behaviours and the outcomes of those behaviours. All of these factors, including living without adequate housing, income, and supports, can influence an individual's mental health and use of substances.

While our personal role—the role of the individual—is always important, the factors that influence health and wellness in ourselves and our community go far beyond individual choices or even individual capacities. For instance, the risk and protective factors that impact resilience, our ability to rise above or bounce back from adversity, do not reside only within ourselves. Many of the most important factors relate to our relationships (e.g., family, friends) and aspects of our community environment (e.g., norms, availability of resources and supports, economic conditions and access to mental health assistance and to alcohol or other drugs).

Homelessness, mental health and substance use

Human experience is complex. Our choices and behaviours, including using substances, are influenced by numerous factors including our biology, our history and social values, and the physical and social environments we live in. People have been using a wide variety of psychoactive (mindaltering) drugs for thousands of years to celebrate successes; to help deal with grief, sadness, and other uncomfortable feelings; to mark rites of passage and to pursue spiritual insight. Drug use is deeply embedded in our cultural fabric. As a complex human behaviour, substance use requires that we look at it from a broad perspective that considers many factors, including our living conditions and our mental health. This includes factors such as pain relief, loneliness, trauma, difficult feelings, or the desire to feel good. These same factors impact people who are homeless in similar and yet, profoundly different ways.

People with poor mental health or who have a mental illness are more vulnerable to homelessness. People living with a mental illness, particularly one that is serious and persistent (such as schizophrenia), experience increased stress that can impact their ability to rebound from the economic, health and social struggles that are a part of the homeless experience. They frequently have low incomes and can experience difficulties finding and maintaining employment. They may have fewer supports in times of difficulty.

Many people who are homeless have significant experiences of trauma. These experiences can lead to poorer mental health and substance use to alleviate psychological pain and emotional suffering. Institutionalized racism has significantly contributed to multi-generational trauma for Indigenous Peoples separated from their lands, homes, and culture. Experiences in the residential school system also remain part of the trauma carried within survivors and their families. These factors, along with poverty, contribute to the over-representation of Indigenous Peoples who experience homelessness. Homeless Indigenous people regularly report experiences of racism within daily life. In these ways, mental health and well-being is often severely compromised.

Being homeless can also foster poor mental health through feelings of fear, anxiety, and isolation that can result in depression and poor sleep. People who do not experience mental health issues while housed can experience poor mental health if they become homeless. This is due to the risks and stresses inherent in the homeless situation. Substance use may begin, or patterns of use change, to cope with these feelings and a changed living situation. People who are homeless and inject drugs are at increased risk of overdose and death. These risks are further complicated for homeless people by racialized and class-based experiences of stigma and discrimination.

Many people who live outside, use shelters, or attend support services conduct a large part of their lives in public spaces. This means that they must often do in public what others do in their homes. Without a place they can enter, close the door and have privacy, homeless people may eat, sleep, wash, urinate and defecate, have sex, use substances, socialize with friends, cry, argue, and conduct myriad other aspects of everyday life under the gaze of others. Some behaviours, including using substances, when conducted in public can lead housed people to make assumptions and generalizations about homeless people. Often, such assumptions are made in light of misunderstandings of the nature of homelessness. These negative and ill-based assumptions lead to the stigma that plays a significant role in the lives of homeless people. Further, housed people, seeing behaviours normally conducted in private, may call the police to enforce laws against intoxication, injecting drugs or congregating in public when there is little option for homeless people to do otherwise. Sometimes, more laws are enacted to deter these behaviours. Criminalization of homeless people and homelessness further limits access to life needs and challenges the right to exist.

People make places, and places make people

One way we can work together to improve the health and well-being of our communities is to collectively recognize that mental health and substance use occur within the context of homelessness and housing insecurity in ways that are both similar to and different from people that are housed. We must move beyond acceptance of mental health and substance use concerns, to focus on what really matters—providing housing, income and supports to reduce the risks and harms related to homelessness. When people are housed and have access to needed supports, their physical and mental health significantly improves, and well-being is possible.

Communities can contribute to reducing the risks and harms related to homelessness by promoting a culture of inclusivity and responsibility among citizens, and by addressing the social and economic conditions that lead to homelessness, poor mental health and risky drug use. For people who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless, this means working toward communities where

-

everyone has access to safe, secure, adequate, and affordable housing (this requires a range of housing options to meet different needs),

-

everyone has access to adequate health and support services (these include mental health and substance use treatment and support options, medical and dental services with expanded hours, access to a safe supply of drugs),

-

everyone has an income adequate to address their life needs (this requires some mix of a guaranteed livable income, adequate income assistance and pension levels and appropriate minimum wage laws that provide for an adequate standard of living),

-

everyone is encouraged to engage in self assessment and maintain balance in their lives (this can be done through common messaging like "not too much, not too often, only when safe" that does not single out certain groups, e.g., people who are homeless or living in poverty) and

-

people are referred to and speak about themselves in non-stigmatizing ways that acknowledge diversity and promote inclusion.

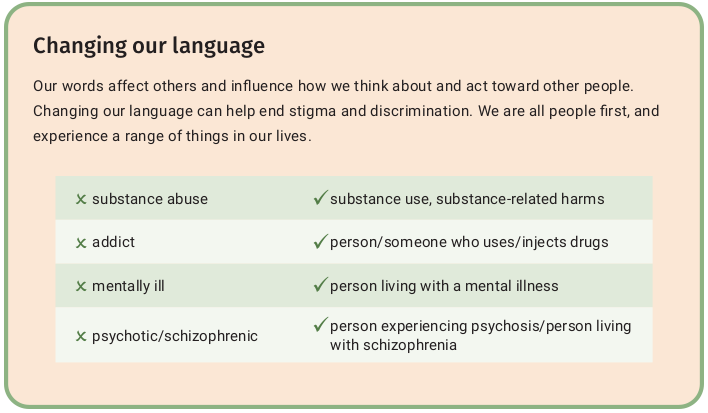

The text of this image says: Changing our language

Our words affect others and influence how we think about and act towards other people. Changing our language can help end stigma and discrimination. We are all people first, and experience a range of things in our lives.

-

Instead of substance abuse, use substance use or substance-related harms

-

Instead of addict, use person/someone who uses/injects drugs

-

Instead of mentally ill, use person living with a mental illness

-

Instead of psychotic or schizophrenic, use a person living with psychosis or a person living with schizophrenia

Health promotion in practice

Health promotion focuses on both healthy public policy and community action, rather than just preventing or "fixing" problems at the individual level. Policy and institutional failures at all levels, combined with societal issues such as structural racism and personal vulnerabilities underpin homelessness. People living with a serious mental illness, Indigenous Peoples, and youth exiting the foster care system are more vulnerable to homelessness. Many thousands of people are homeless each year and, while most are unhoused for short periods, some experience long-term homelessness and a range of health concerns.

Lack of safe, affordable, adequate housing is a primary driver of homelessness. A first line of good public policy enables and supports provision of housing and income adequate to address life needs. This, together with health care and other supports, allows people to achieve well-being. When the extreme stresses of living homeless are relieved and daily life is not about survival, health improves and people have the physical and psychological space to address other concerns, be it arthritis, heart disease, loneliness or substance use. Mental health and substance use concerns may then take their place as bumps, blips, or perhaps, boulders along the life course, rather than issues that can lead to illness, injury or death when living homeless. This process takes time, often years. When healthy policy such as a national housing strategy is implemented, and where there is suitable housing for everyone, well-being improves for all.

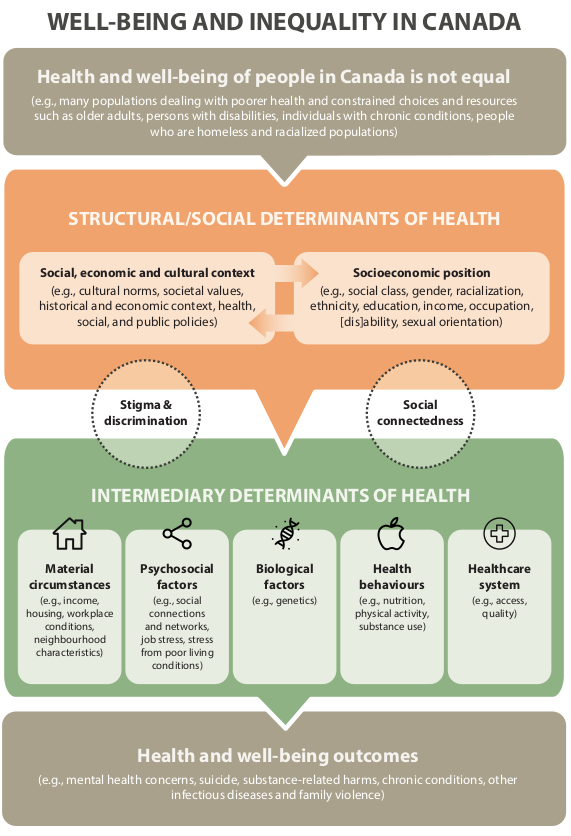

The title of this infographic is: Well-Being and Inequality in Canada. It shows how systems-level factors impact individuals.

Health and welling of people in Canada in not equal—e.g. many populations dealing with poorer health and constrained choices and resources such as older adults, persons with disabilities, individuals with chronic conditions, people who are homeless and racialized populations.

Structural/social determinants of health: the social, economic and cultural context people live in as well and their socioeconomic position are connected.

-

social, economic, and cultural context: e.g. cultural norms, societal values, historical and economic context, health, social and public policies

-

socioeconomic position: social class, gender, racialization, ethnicity, education, income, occupation, disability, sexual orientation

These factors impact intermediary determinants of health. They are also influenced by stigma, discrimination, and social connectedness.

Intermediary determinants of health: material circumstances (e.g. income, housing, workplace conditions, neighbourhood characteristics), psychosocial factors (e.g. social connections and networks, job stress, stress from poor living conditions), biological factors (e.g. genetics), health behaviours (e.g. nutrition, physical activity, substance use), health system (e.g. access, quality).

These factors impact health and well-being outcomes (e.g. mental health concerns, suicide, substance-related harms, chronic conditions, other infectious diseases and family violence)

Adapted from: From risk to resilience: An equity approach to COVID-19, Chief Public Health Officer of Canada's Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2020.

†"Determinants" or "social determinants" are used interchangeably for the "social determinants of health."

References

- Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness (2020). One in five Canadians have a friend or acquaintance who has been homeless; majority support building new affordable housing. National Survey conducted by Nanos for CAEH, August 2020. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/caeh/pages/81/attachments/original/1597194371/CAEH-Nanos_Poll_ Report_-_Housing___Homelessness_%281%29.pdf?1597194371=

- Dunn, J. (2002). Housing and inequalities in health: A study of socioeconomic dimensions of housing and self reported health from a survey of Vancouver residents. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 56, 671-681.

- Gaetz, S.; Barr, C.; Friesen, A.; Harris, B.; Hill, C.; Kovacs-Burns, K.; Pauly, B.; Pearce, B.; Turner, A.; Marsolais, A. (2012) Canadian Definition of Homelessness. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press.

- Norman, T., Pauly, B., Marks, H., & Palazzo, D. (2015). Taking a leap of faith: Meaningful participation of people with experiences of homelessness in solutions to address homelessness. Journal of Social Inclusion, 6(2), 19-35. https://doi.org/10.36251/josi.82

- World Health Organization. (1946) Constitution of the World Health Organization, Off. Rec. Wld Hlth Org., 2, 100, amend to WHA51.23 (2005). https://www.who.int/about/accountability/governance/constitution

Other sources

- Amster, R. (2008). Lost in space: The criminalization, globalization, and urban ecology of homelessness. LFB Scholarly Publishing.

- Applebaum, L. (2001). The influence of perceived deservingness on policy decisions regarding aid to the poor. Political Psychology, 22(3), 419-442.

- Bloom, A. (2005). Toward a history of homelessness. Journal of Urban History, 31(6), 907-917.

- Bogard, C. J. (2001). Claimsmakers and contexts in early constructions of homelessness: A comparison of New York City and Washington, D.C. Symbolic Interaction, 24(4), 425-454.

- Bryant, T. (2009). Housing and health: More than bricks and mortar. In D. Raphael (Ed.), Social determinants of health (Second ed., pp. 235-249). Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

- Drug & Alcohol Findings (2020). Dignity First: Improving the lives of homeless people who drink and take drugs. Retrieved from: https://findings.org.uk

- Gaetz, S. (2017). New direction: A framework for homelessness prevention: Summary. Homeless Hub.

- Gaetz, S., & Marsolais, A. (2014). State of homelessness in Canada 2014. Homeless Hub. Graham, H. (2004). Social determinants and their unequal distribution: Clarifying policy understandings. The Millbank Quarterly, 82(1), 101-124.

- Gustafson, K. (2009). The criminalization of poverty. The Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 99(3), 643-716.

- Kingfisher, C. (2005). How the housed view the homeless: A study of the 2002 controversy in Lethbridge. Lethbridge, AB: University of Lethbridge.

- Kyle, T., & Dunn, J. R. (2008). Effects of housing circumstances on health, quality of life and healthcare use for people with severe mental illness: A review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 16(1), 1-15.

- Lynch, J., & Kaplan, G. (1997). Understanding how inequality in the distribution of income affects health. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(297), 314.

- Lyon-Callo, V. (2000). Medicalizing homelessness: The production of self-blame and self-governing within homeless shelters. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 14(3), 328-345.

- Lyon-Callo, V. (2008). Inequality, poverty, and neoliberal governance: Activist ethnography in the homeless sheltering industry. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- McDonald, L., Donahue, P., Janes, J. and Cleghorn, L. (2009), “Understanding the health, housing, and social inclusion of formerly homeless older adults”, in Hulchanski, J.D., Campsie, P., Chau, S., Hwang, S. and Paradis, E. (Eds), Finding Home: Policy Options for Addressing Homelessness in Canada. Toronto: Cities Centre Press.

- Marvasti, A. (2002). Constructing the service-worthy homeless through narrative editing. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 31, 615-651.

- Mikkonen, J., & Raphael, D. (2010). Social determinants of health: The Canadian facts. Toronto: York University Press.

- Moeller, S. (1995). The cultural construction of urban poverty: Images of poverty in New York City, 1890-1917. Journal of American Culture, 18, 1-16.

- Navarro, V. (2007). What is a national health policy? International Journal of Health Services, 37(1), 1-14.

- Public Health Ontario (2019). Homelessness and health outcomes: What are the associations? https://www.publichealthontario.ca

- Raphael, D. (2007). Poverty and policy in Canada: Implications for health and quality of life. Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press.

- Raphael, D. (2009). Social determinants of health: Overview and key themes. In D. Raphael (Ed.), Social determinants of health (Second ed., pp. 2-19). Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press.

- Raphael, D. (2016). Social determinants of health: Canadian perspectives (Third ed.). Canadian Scholars' Press.

- Scheff, T. J. (1984). Being mentally ill: A sociological theory (2nd ed.). New York: Aldine Publishing.

- Susser, I. (1996). The construction of poverty and homelessness in US cities. Annual Review of Anthropology, 2, 411-435.

- Thomson, H., Petticrew, M., & Morrison, D. (2001). Health effects of housing improvement: Systematic review of intervention studies. BMJ, 323, 187-190.

- Willse, C. (2010). Neo-liberal biopolitics and the invention of chronic homelessness. Economy and Society, 39(2), 155-184.

About the author

The Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, formerly CARBC, is a member of the BC Partners for Mental Health and Substance Use Information. The institute is dedicated to the study of substance use in support of community-wide efforts aimed at providing all people with access to healthier lives, whether using substances or not. For more, visit www.cisur.ca.