A brief introduction

We often think of health in a "pathogenic" frame, that is, as not suffering from disease and of mental health as the absence of a psychological illness or mental disorder.

In the last century medical historian H.E. Sigerist recognized that health is more than the absence of illness, it is social conditions that result in a "balance between work, rest, recreation, and wages that permit a decent standard of living."1 In the same vein, the World Health Organization (WHO)2 defines health with a more "salutogenic" thrust as a state of physical, mental and social well-being on both collective and personal levels. What would such a defifinition include if it were part of day to day life?

On an individual level, mental health may be thought of as a state in which one "realizes his or her abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community."3 A broader definition might describe mental health as “the capacity of each and all of us to feel, think and act in ways that enhance our ability to enjoy life and deal with the challenges we face. Mental health then is a sense of emotional and spiritual well-being that respects the importance of culture, equity, social justice, interconnections and personal dignity."4 Are there other views that might contribute to our understanding of mental well-being?

Keyes5 highlighted the notion of flourishing as integral to mental health. Flourishing transcends the issue of whether or not a mental illness is present to focus on positive emotional states with effective psychological functioning (self-acceptance, personal growth, purpose, environmental mastery, autonomy, good relationships) and social participation (social acceptance, actualization, contribution, and integration). A mentally healthy population would then be one in which personal and environmental influences are mostly positive and where, over time, an increasing percentage of individuals achieve a greater quality of life. How might this broader understanding of mental health fit within a health promotion perspective?

Health promotion has been described as the process of enabling/empowering individuals and communities to gain control over the determinants of health6 and thereby improve their health.7 Central to this pursuit are ideas of participation, empowerment and equity. Health promotion might then be thought of as building connectedness and literacy, since mutually supportive relationships and acquired skills are vital to enhancing public well-being and, thereby, mental health.

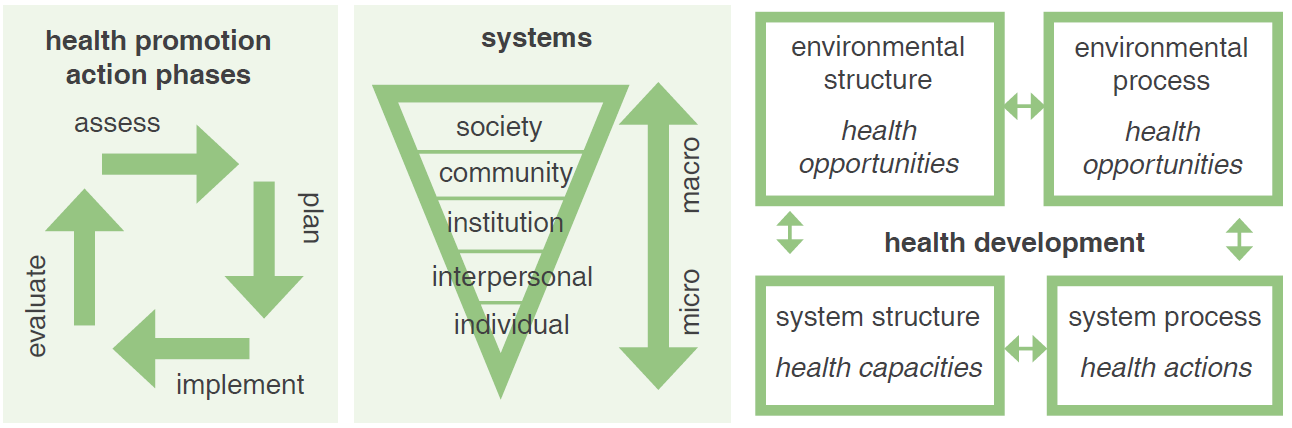

A social-ecological model of public health and health promotion reflects the complexity and dynamic interplay among a number of factors. These factors operate within and across levels from the individual through to society as a whole such that environments affect people personally and as a community. Conversely, individual and collective action impacts social environments including the family and the community. The social-ecological model likewise respects that intervention can be made at a variety of points and in a range of ways that strengthen resilience and remove or reduce challenges. Complementary activity on several fronts can produce greater benefit than initiatives concentrated in one area. As such, the model calls for interdisciplinary collaborative efforts to address the diversity of issues that bear on the health of a community and its people.

A matrix has been developed to aid in determining and directing strategies that can together form a coherent response to effect positive change in the settings of concern.8 For mental health, this involves applying health promotion action phases to a mental health issue within two of the system areas by acting on influences and so changing outcomes. The process is illustrated below.

This simplified rendering of a social-ecological approach to health promotion for mental health draws broad strokes that describe what is in reality a more complex system of inter-related outlooks and actions. Thinking of how these ideas can or have been implemented in your community or on your campus, how might mental health be addressed other than just intervening on an individual level? What steps (including policy stances) have been or might be taken to mitigate factors contributing to mental health problems and strengthen elements resistant to such problems?

For more information on this and other topics related to well-being in British Columbia campus communities, please see the Healthy Minds | Healthy Campuses website at https://healthycampuses.ca/. A recent example of work done at Vancouver Community College related to mental health and supported by Healthy Minds | Healthy Campuses may be seen at https://healthycampuses.ca/mental-health-and-well-being-framework/.

Footnotes:

-

Fee, E. (1989). Henry E. Sigerist: From the Social Production of Disease to Medical Management and Scientic Socialism. The Milbank Quarterly. Vol. 67, Supplement 1. Framing Disease: The Creation and Negotiation of Explanatory Schemes (1989), p. 136.

-

WHO (2022). Geneva Charter for well-being. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/health-promotion/geneva-charter-4-march-2022.pdf

-

WHO (n.d.) Mental health: strengthening our response. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response, accessed March 3, 2023.

-

Joubert, N. & Raeburn, J. (1998). Mental health promotion: People, power and passion. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 1(Inaugural Issue), p.16. http://drnatachajoubert.com/documents/Peoplepowerandpassion.pdf.

-

Keyes, C. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207-222.

-

This includes housing, income and social status, access to health services, education and literacy among others. Please see: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/what-determines-health.html for a more complete listing.

-

WHO (2005). Bangkok Charter for health promotion in a globalized world (p. 1). https://www.afro.who.int/publications/bangkok-charter-health-promotion-globalized-world. That statement repeats and adds to the formulation in WHO (1986) Ottawas Charter for health promotion (p. 1). https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/129532/Ottawa_Charter.pdf.

-

Bauer, G., Davies, J., Pelikan, J., Noack, H., Broesskamp, U. & Hill, C. (2003). Advancing a theoretical model for public health and health promotion indicator development. European Journal of Public Health, 13(3), 107-113.

References:

-

Stokols, D. (1996). Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion, 10(4), 282-298.

About the author

The Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, formerly CARBC, is a member of the BC Partners for Mental Health and Substance Use Information. The institute is dedicated to the study of substance use in support of community-wide efforts aimed at providing all people with access to healthier lives, whether using substances or not. For more, visit www.cisur.ca.