"Blips and Dips in the Recovery Journey" issue of Visions Journal, 2019, 15 (2), pp. 14-16

A few years ago, I was in a different, darker place in my life.

Every night, I would sit in a dimly lit room in Victoria, BC, alone at my desk, drawing or writing. I was invisible in a city where almost no one knew me. I told myself I was comfortable there. The nights were long, the work was hard and I could be alone with my thoughts. During those long, solitary nights, if a tear were to fall from my eye, it would strike the bottle of alcohol that I cradled in my trembling hand. This was the poison that had imprisoned me in this small, quiet corner at the edge of the planet, there on the island I called home. But at that time, eight months sober, I had resolved not to open that Last Bottle.

One night, I found myself clinging again to that Last Bottle. It glared at me under the light of my desk. Whatever small spark of strength I had left waned in the presence of that bottle. I felt angry at a world that had abandoned me. I felt disgusted by my selfish feelings and my weakness. I felt sorrow, I felt loss. I placed the bottle on the desk before me. It was too heavy. It wasn’t simply a bottle of alcohol. It symbolized much more than that. Its weight had become too much to bear.

I felt utterly and completely alone.

For some reason, in that moment, I picked up the phone. I called one of the few people I felt I could trust. Someone I knew might listen, someone who might possibly talk me out of reaching for the bottle opener on the desk.

The person I called was in bed; I had likely woken them up. I wasn’t even sure what to say. Through the hurt, pain and fear, I started talking. I felt like a mess, babbling, incoherent. I explained what was happening and what I was at risk of doing next. I felt powerless. It was a terrible feeling. I didn’t expect the person to understand, but I kept talking anyway. I knew enough to know that I couldn’t be alone in my head at that moment. I needed to remain accountable. Even if no one else cared what I did when I was alone, I would know.

That phone call saved me that night. That person was there for me.

Trading one cycle for another

The process of my recovery has been a long one, and there have been setbacks along the way—including the relapse that I described above. Over that period, there have been several important factors in my efforts to disrupt the cycle of alcoholism and become a healthier person. One was cycling.

When I started riding a bike, I immediately felt the mental health benefits. I had lived with major depression for half my life, and I started to see there was a link between cycling and how I felt on a daily basis. I would feel the endorphins on a good, long ride, and that would affect my mood and, in turn, my body. As I started to feel better, I started to feel more motivated to keep pushing myself to see what would happen next. I began to challenge myself to go longer distances and to get myself working harder.

Eventually, I had shed tears and sweat across thousands of kilometres. Climbing the hills that ripple across Vancouver Island built a physical and mental strength that I had not previously known. The discipline of riding almost every day meant that over time I developed my ability to ride farther and faster. I started half-seriously referring to myself as an athlete; the title gave me a sense of mastery over my choices. My sleep improved; I began to eat better. I lost 130 pounds and was able to manage my type 2 diabetes. And my depression began to lift.

Honouring self, past and present

Another important factor in my recovery process has been reaffirming and honouring my Indigenous identity and heritage—something that has particular significance as I take on the task of personal healing.

I am Anishinaabe, from what is now called Manitoba. In Manitoba particularly, Indigenous peoples have not had an easy time. I myself am a Sixties Scoop survivor. Very shortly after I was born, I was forcibly separated from my biological parents by a government agency, removed from my community and adopted by a non-Indigenous family. As a result, I lost all connection to my language and my culture.

Today, most people in Manitoba don’t really understand what a Treaty is or that, for the Anishinaabe, there is no life without the land on which to live it. This fundamental relationship that the Anishinaabe have with the land is broken; the impact of that has been felt mentally, physically, emotionally and spiritually for many generations. But these issues have never been properly addressed by the provincial or federal governments. Colonization has been allowed to flourish, and there is no real way forward until the reasons for that are acknowledged and the problems that stem from colonization have been resolved.

As an Indigenous person, I have not found counselling to be particularly helpful—at least, not the counselling typically offered by our current mental health services. The counselling I’ve received lacks substance and cultural sensitivity and understanding about Indigenous issues and the factors that affect Indigenous mental and physical health outcomes. As much as I want to encourage Indigenous people to find a professional to talk to if they need it, there are a lot of gaps in the current mental health system when it comes to providing adequate services for Indigenous clients. I’ve also had Indigenous people report to me that they have a hard time even accessing basic services, let alone services that are meaningful to them.

It’s easy to see how Indigenous people are overlooked, viewed as inferior or with pity. Our wisdom, our history and our culture are in the process of being extinguished. If our ways were viewed in the holistic, democratic and community-driven ways they were intended to be viewed, and practised in the way they were traditionally practised, then I think that our people—no matter their age, gender or sexual orientation—would experience the benefits of inclusive, culturally sound mental health practices.

As a nomadic people, the Anishinaabe used to continually move around the prairie. While I may have romantic notions of chasing buffalo and riding horses all day, I know that it took community, determination, hard work and discipline for our Nations to survive and flourish. When I am cycling now, on a group ride or on my own, I exercise the same principles. When I ride, I think that my ancestors see me and are pleased. There’s no better way for me to connect with my Anishinaabe roots than doing that work, owning that effort and that pain. I feel freedom when I ride, and I like to think that I get a taste of what my ancestors knew.

The art of recovery

Several aspects of becoming sober have been attractive and affirming for me. My friends who live far away could hardly believe I’d stopped drinking. I felt their admiration. The messages were positive. People saw the new me, and they liked it. But I wasn’t trying to be sober for anyone else. I had embarked upon this journey for me and my future dreams.

I began to tell my story through art. I worked to develop a better relationship between my brain, my eyes and my hand, with a pen nestled comfortably between my fingers. These drawings felt like the best way for me to communicate with the outside world. I sold a few of my drawings to complete strangers. My adoptive mother encouraged me to keep going.

I decided to seriously pursue art as a career. It was an ambitious goal, but I already had a framework: I applied the same discipline that I had applied in my cycling and my recovery from alcohol addiction to developing and maintaining my artistic practice.

I was applauded for making better choices. It was a great feeling. But like recovery and physical fitness—and any other challenging pursuit—eventually the applause died down. Once the initial wonder and admiration subsided, I was no longer in the spotlight and people moved on.

Soon enough, the darkness returned to challenge me once again, and I found myself battling familiar demons. That’s the way depression works.

But as an artist, I started to appreciate the pattern, watch it with an artist’s eye. I realized that it’s important to observe the storm clouds rolling in. It’s important to acknowledge their force and potential for causing damage. I started to better understand how to prepare for the darkness and the oncoming storm. There will always be moments when we face disappointment or rejection; in the past, I have turned to the safety of alcohol because it ends the negative feelings. Now that I no longer use alcohol to cope, the pain can feel sometimes as if it is amplified. It is a monumental challenge to deal with that pain in a meaningful and healthy way.

But then I remember that night long ago, when I reached out and made that phone call. In that moment I knew the nature of relapse. Relapse is the feeling of being lost. That state was fuelled by my loneliness—needing, but not having, human connection. Even then, I knew instinctively that when a person’s basic needs are not met, they are vulnerable to old habits. I knew I needed encouragement. I needed to know that my absence would be felt. That night, I looked beyond myself and found a voice in the darkness.

All it took to snap out of my relapse was to talk. To believe in the possibility that tomorrow would be a new day. When the call ended, I felt appreciation and gratitude. I let myself feel the dark feelings. I observed them the way an artist observes the storm roiling across the sky and over the horizon.

At some point during the telephone conversation, the bottle that I held in my hand had fallen under the bed. It had lost its dominance over me. It was just a ghost. Nothing more.

About the author

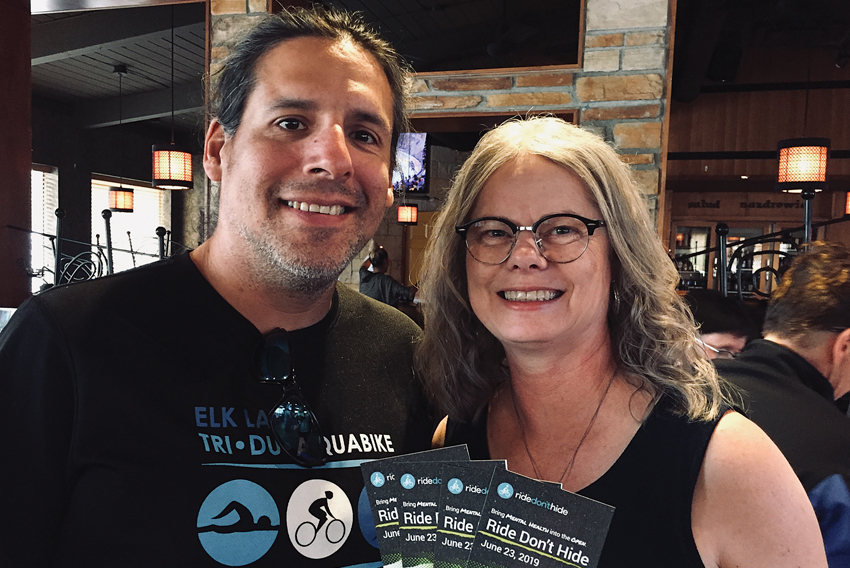

Mike is an Anishinaabe triathlete and artist, originally from Swan Lake First Nation. When not illustrating graphic novels, writing or painting in his current home of Kamloops, BC, Mike spends the best moments of the day with his loving partner Natika