Reprinted from the Housing as a Human Right issue of Visions Journal, 2022, 17 (2), pp. 30-31

Just as the pandemic has been challenging for the general public, it has been exceptionally so for many health professionals. Working as a family doctor based out of a community clinic and hospital in Surrey, I have found it heartbreaking to watch nurses and physicians leave their beloved work posts due to exhaustion—taking early retirement, using medical leaves or just walking away.

Having experienced work related burnout and exhaustion myself a few years ago, part of me is happy for my colleagues’ courageous decisions to step away from the fire of the frontline to heal. The other part of me asks why so many of us in the helping professions have a tendency to keep giving until we have completely depleted our own reserves of wellness.

Pre-pandemic, a toxic culture of perfectionism and blame in many hospitals and clinics had already exposed their most compassionate front line workers to health and wellness threats. In that culture, those who make very human mistakes are criticized in behind-the-back chats and slowly isolated until they lose all sense of purpose in their work. Some medical staff do not feel psychologically safe to point out errors or share ideas for improvement with fellow team members for fear of being frozen out.

And in a poorly integrated system where demand for quality services far outstrips supply, leaders of each area of our medical system were at odds, competing for money, space and human resources. This is a divided or “siloed” system, with each silo playing zero sum games of optimizing the assets of their silo, rather than considering the system as a whole. This makes it easy to blame “others,” and problems are attributed to neighboring silos.

Entering into the pandemic then, many health professionals were already exhausted, without much capacity to shift up a gear. Pre-pandemic, many of my nurse colleagues were already burnt-out and becoming emotionally disconnected just to survive daily traumatic exposures and abusive encounters with people attending the ER and clinic. Pre-pandemic, family doctors were already working eight-hour clinic days, then giving up time with their families to add three more hours entering data from clinical encounters into their medical record software, while in their pajamas, before low quality sleep.

When the pandemic called for major shifts in clinic and hospital operations, all of these pre-existing problems got worse. On top of the COVID-related workload, our clinics and hospitals saw significant spikes in the number of patients desperate for mental health and substance use therapies. We scrambled to connect patients to the right services. Patients’ distress and trauma created indirect, or what is called vicarious distress for already-traumatized health care staff.

To watch my patients try repeatedly to access mental health services that are not designed to meet them where they are at (unacceptable wait-times, wrong language, wrong time, wrong place, feels unsafe, not in-person) has been deeply distressing. I estimate that only a small minority of health professionals were given adequate training to process and heal vicarious distress. For caring people, watching other people experience distressing outcomes repeatedly despite best efforts adds to burnout.

Medical culture emphasizes the ideal of the “health professional as martyr.” Many times, the leaders we caregivers admire are those who sacrifice their own wellness for the needs of the team or patients. Many health professionals work 50- to 70-plus–hour weeks, rarely because they enjoy it. Often this is what was modelled for them by their mentors. Other times, they do it to keep up with the Joneses. Some pull back-to-back shifts to maximize financial payout at a cost to their own health and, potentially, what they can bring to each patient they serve.

All of this is at war with the rest and compassion that our bodies demand to function optimally. As our system evolves from downstream illness care, to care that supports wellness upstream, we are overdue for a parallel shift from the “health professional as martyr” ideal to one of “health professional as champion of compassion for self and for others.”

I bought into the ideal of the martyr early in my career. In my first five years I overworked and said yes to every patient who came through my door. I sacrificed my time with my family and my family’s experience of me in order to serve my patients and clinical work. I neglected my self-care and the needs of my body in order to keep up with the culture of primary care in a fee-for-service, rush-the-patients-through-the-factory world. Living this unsustainable lifestyle of overwork only reduced my capacities and the quality of my work.

Our medical and non-medical communities harbour prejudices towards mental health and substance use challenges. This stigma makes it harder for people who need help to ask for it.1 It also keeps the medical community unwell. People punch in but figuratively limp along, with simmering illness waiting for a reason to emerge. In my case, it took developing flares of autoimmune disease before I slowed down. Over the past few years, I have built up the courage to share my journey of burnout with my peers in speaking engagements. Invariably, afterwards, peers share similar journeys of burnout and recovery.

For me, the element of the pandemic that has most exacerbated the pre-existing exhaustion of health professionals has been the public’s trust of conspiracy theories over the opinions of compassionate, diligent health professionals. But, upon reflection, I can see that medical culture has not prioritized effective communication that outcompetes viral misinformation. How can we blame the public for not having a discerning lens through which to filter facts from conspiracy?

As a mentor of mine, Paul Batalden, once said, every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.2 And as Dr. Maya Angelou said, “When you know better, you do better.”3 My hope is that BC’s commitment to psychological and cultural safety will provide a framework for leaders to heal the culture of medicine. Meanwhile, I call on health professionals to make it their priority to speak more authentically with other professionals, with their families and with their friends about their struggles.

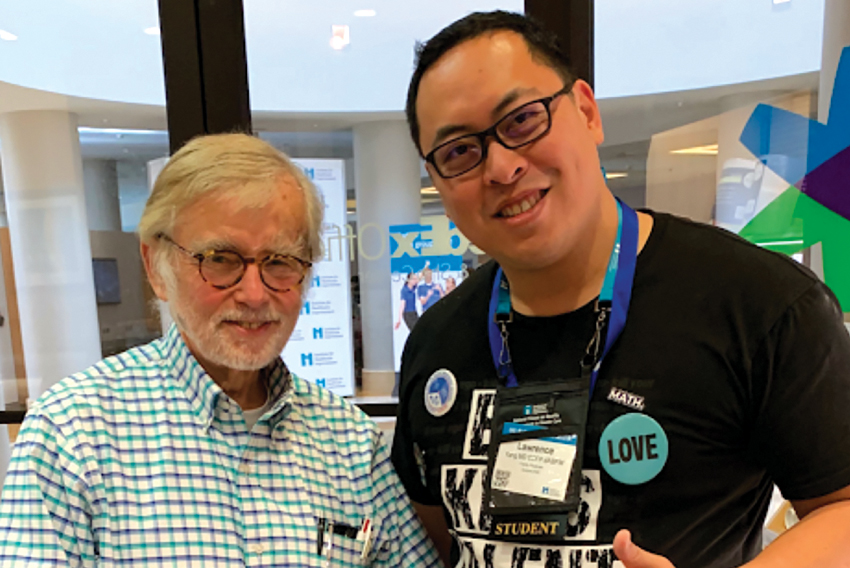

About the author

Lawrence is a family doctor and current chair of the Wellness Committee at Surrey Memorial Hospital. As a quality improvement coach, he enjoys working with teams of compassionate listeners doing their best to assist people to live longer and happier lives

Footnotes:

- Physicians and their families can seek assistance for stress and burnout through physicianhealth.com. They can also reach out by phone: 1-800-663-6729.

- For a history of how Dr. Paul Batalden developed this expression, visit: ihi.org/communities/blogs/origin-of-every-system-is-perfectly-designed-quote

- Quote attributed by Oprah Winfrey to Maya Angelou. See: oprah.com/oprahs-lifeclass/the-powerful-lesson-maya-angelou-taught-oprah-video