Reprinted from the Intergenerational Trauma issue of Visions Journal, 2023, 18 (2), pp. 35-36

I became a community builder and it saved my life.

I was born Acadian, in poverty. Poverty is painful. My mom rebelled as an intergenerational trauma survivor. I was raised by a single mom on welfare with my mixed-lineage siblings, including Métis, in a society that blamed and punished Mom and all of us. I was third-born of four, adding to the line. I had no idea who I was, where our ancestors were from or how we ended up in Winnipeg.

Growing up I saw working-poor people and many poor Indigenous people around me, suffering. Later, I learned that having been displaced on their own territory, many were forced to wander and seek. I also heard stories from neighbours who were survivors of two world wars. There were also other settlers whose lineage is predominantly known as “white.” White is not a race (which, itself, is a construct), it’s a strange colonial system of power that has affected my life from its very beginnings to this very day, sitting here writing.

By age nine, I knew what to expect, what to watch out for and to try to get away. At that time, I had the fear of being beaten by my mother’s then-husband, also an intergenerational trauma survivor. By age 13, in my teenaged mind, I lived in a world that offered me pain, sorrow, an ugly authoritarian state and inequity. This created such suffering and poverty that I had seen enough. I could not explain that the world seemed so messed up it made me want to kill myself. It seemed there was no way out. Living in poverty, it can feel like that a lot of the time.

How would I ever have known at 13 that I would make it through suicidal ideation? I never believed I would get past being “a teenage runaway.” I made it through child and young-adult sexual abuse...I figured I could survive running away. But to make it through the shame: would I survive that? By my early twenties, I had been a drug user for about six years. I almost died using an elephant tranquilizer (carfentanil), but ended up in detox instead.

There, I was offered shelter, treatment and weekly therapy for a year. It was free—and sensational. After one year of therapy, the counsellor asked me, “Do you think it’s possible that your drug and alcohol use helped you get through the hard years and kept you from killing yourself?” I knew it was true as soon as she asked. That’s what I would do: get so freaked out and down and out about the reality of the world—economics, wars, hunger, suffering, fear of being hurt even more—and I’d use and drink to bury those worries and drown them out until I could deal with a life-long heal.

Healing intergenerational trauma

How do I express how it is that I got here, close to retirement age? I am an example of how many of us heal through community care and grassroots, supportive agencies—not overbearing soft incarceration, a term many of my peers use for high-security shelters. I healed with other peers, all of us learning together.

Unfortunately, the “clean and sober” model is a set-up for most. I healed through learning about the past. What was before? Why did my life take this trajectory? We forget that there was a time when we did not have a police state dictating what or who is criminal. Since then, we’ve seen intergenerational trauma, generational abuse, child sexual abuse by strangers and family.

Intergenerational trauma is absolutely frustrating. It’s frustrating because everything you go for in society is that much harder than it is for others. Community is where the most potential exists for healing. If you have proximity to your community and proximity to supportive services that don’t dictate, but offer solutions, you can heal. No matter how messed up a person seems, they always do better in the community they choose.

In the 1980s I was part of a movement to “break the silence” about sex abuse. That strengthened me. In the 1990s I healed by sharing my story with other survivors and in public. Learning about systemic abuse and intergenerational trauma helped me, as a survivor, heal from abuse. Learning from and among peers, as well as learning from others from other lineages and cultures, I learned we have a common struggle. This made me feel a part of a larger whole, a struggle others were in, not just me.

Healing from intergenerational trauma is a lifelong commitment. The benefits are community—if you get supports needed to get through a crisis. Otherwise one crisis builds on another, and nobody can handle that. It just doesn’t always look how most government-run agencies say it will. If we had a harm reduction treatment model available to everyone, we would see more success.

Breaking the cycle

This healing I speak of is not simply personal. It’s about a complicated system that seems to bring many to their knees, generation after generation. We are born into a system of governing that was, and still is, hierarchal, patriarchal, white supremacist, racist and sexist. Why does intergenerational trauma exist? Unnecessary pain and suffering come from systemic oppression. That is at the root.

Breaking the cycles of trauma takes a lot of work. There is often no support for poor people, just punishment models and repeating cycles. Nothing is simple, including the laws that do the punishing. If anything, what has helped me heal was meetings with peers every day, building community. I also had weekly sessions with a counsellor who understood harm reduction. Detox on demand, treatment and community building have helped me and others live good, productive lives.

About the authors

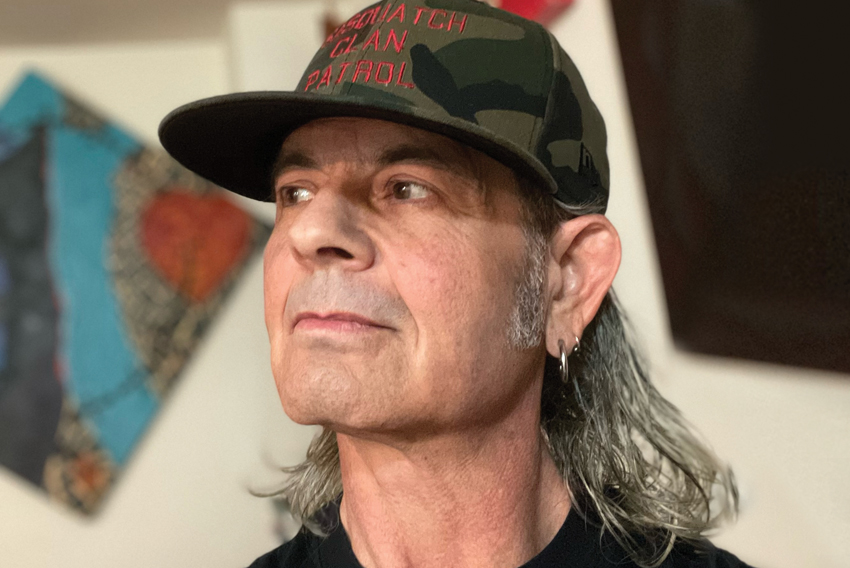

Kym is a settler-Acadian whose family arrived on mi’kmaq territory in 1636. Kym is a transgendered survivor, community organizer, parent and anti-poverty activist who has fought many battles with his peers facing state oppression